Prefer to listen? Press play to hear this article.

When it comes to the conditions, flight planning is a level above flicking through a weather app on your smartphone, with a whole world of codices and abbreviations allowing pilots to receive a wealth of complex data from just a few short lines of text.

By looking at the different types of pilot weather briefings, we can begin to get a sense of the type of information available to pilots before they fly. We’ll then take a brief glance at the ways in which they unpick this intricate web of confusing data, but don’t worry! We’ll leave the detail to the instructors at BAA Training – they’re the experts, after all!

METAR – Meteorological Aerodrome Report

What are they?

Produced at ground level, METARs are routine, everyday weather reports that are essentially observational in nature and seek to guide the pilot towards achieving a broad understanding of the weather conditions that they can expect on their upcoming flight. In short, a METAR depicts the current weather, and is usually valid for a period of one hour.

What do they contain?

As well as routine data common to all aviation weather reports – time of observation, location of airport, etc. – METARs provide a pilot weather briefing consisting of wind, visibility, weather, sky condition, temperature and dew point, altimeter setting, and potential further remarks. This provides the pilot with a quick overview, giving them a rough idea of what sort of sky they’ll encounter once they begin their ascent.

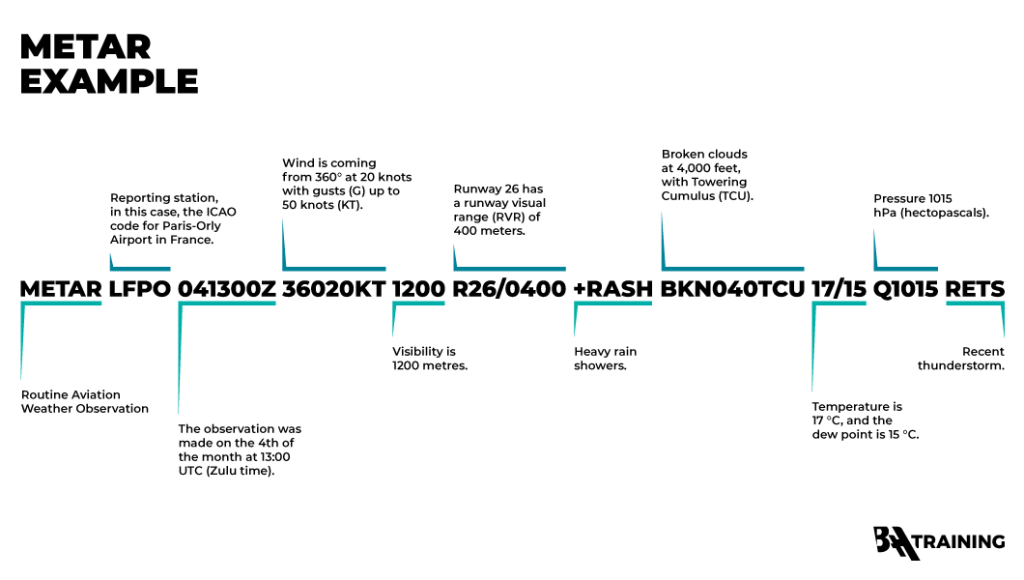

What do they look like?

Packing such a wealth of information into such a small space is one of the key benefits of METARs, but this isn’t without its downside. As the example below depicts, the codified nature of METARs that gives them their brevity also requires a lot of expertise to unpack, with each small unit of data containing a lot of information when decoded. Note that these examples are coloured for visibility here – in the field, given in monochrome.

How are they interpreted?

Once you’ve got your head around how to read METAR data by compartmentalising it like in the example above, you’ve then got to understand what the specific abbreviations themselves represent. There are no shortcuts here: it’s a case of memorising them and building familiarity. With enough expertise, you’ll be able to decode the example above as follows:

TAF – Terminal Aerodrome Forecast

What are they?

In contrast to a METAR, which denotes observed weather, the purpose of a TAF is to aid in flight planning and weather prediction by providing a forecast of what the pilot can expect during their flight. Typically issued for 24- or 30-hour periods, TAFs come not from airports or aviation bodies, but from meteorological authorities that specialise in weather prediction, such as the Met Office in the UK.

What do they contain?

The word aerodrome in the TAF acronym signifies that these forecasts are restricted to a specific locality: typically, a radius of 5 nautical miles around the airport. They involve much of the same identifying data as a METAR, with the key difference being that they’re predictive rather than descriptive.

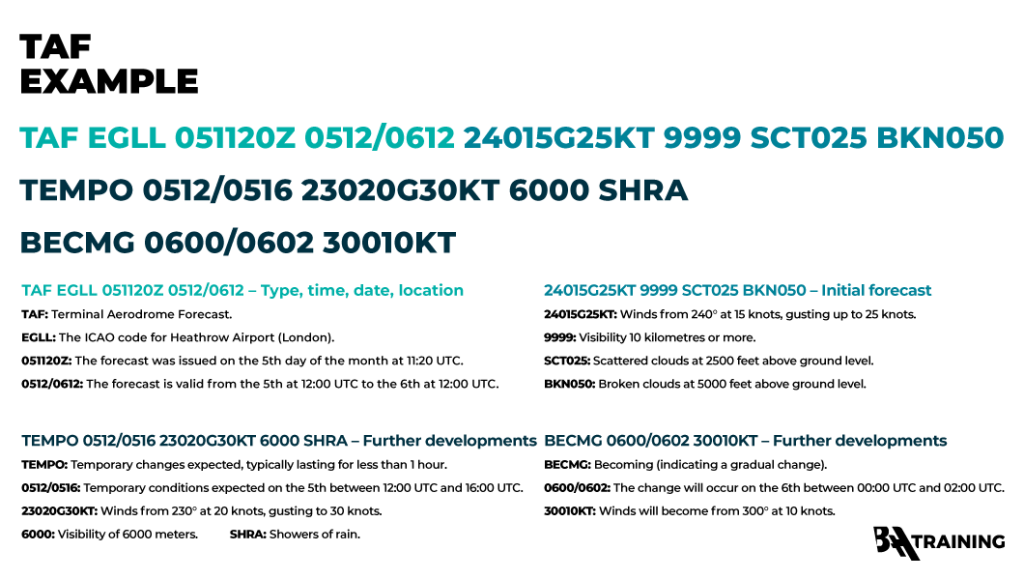

What do they look like?

The similarities between METARs and TAFs aren’t limited to their content, as they also look similar at first glance. To the untrained eye, the information below might look like a hapless jumble of random letters, but to a highly trained pilot it’s the key to a successful flight.

How are they interpreted?

TAFs can be broken down into three distinct areas – identifier data, current forecast, and future developments – before then proceeding with the detail as follows.

PIREP – Pilot Report

What are they?

The key feature of the PIREP is that in contrast to METARs and TAFs, which are produced by ground staff and meteorological services, respectively, the PIREP comes directly from pilots. The first word in the name of a pilot report refers not to the intended recipient – after all, METARs are TAFs are also both written for pilots – but to the author of the report. This means that not only do they report on the conditions that can be expected, but they also do so from the perspective of a fellow aviator, containing key details that only pilots will recognise.

What do they contain?

Much like METARs and TAFs, PIREPs contain key information on the weather and climatic conditions that the departing pilot can expect to encounter, but what distinguishes the PIREP is its ability to also relay information on the pilot’s experience, offering a perspective that no amount of remote monitoring can hope to match. This might include reports of specific ground conditions or atmospheric issues such as turbulence, often adding to the information given by METAR and TAF providers.

What do they look like?

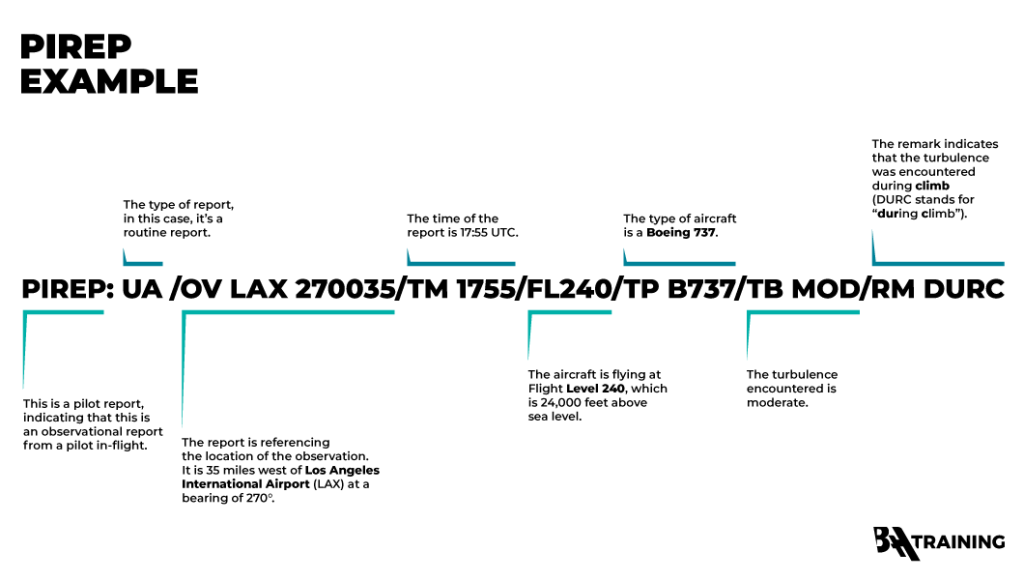

As the example below shows, a now familiar string of coded letters and numbers makes up a PIREP, with some subtle differences based on the type of information that can be conveyed.

How are they interpreted?

Your PILOT CAREER

starts with a first click

In much the same way as a METAR or a TAF, the PIREP is broken down into a series of blocks that each convey specific information. In the case of the example above, this is as follows:

ATIS – Automated Terminal Information Service

ATIS is slightly different from the three types of report that we’ve already considered, as the data that it provides is a lot more comprehensive. These packets of information are put out on a frequency that continuously broadcasts to pilots in order to keep them informed.

It’s not just weather, though – ATIS also includes data on runways, ground conditions, and any other key points that the pilots should be made aware of. The broadcast is updated once per hour by the air traffic controllers that are charged with compiling ATIS data, ensuring that it always provides the fullest, most up-to-date picture for those who need it.

The similarities between METARs and ATIS data often cause confusion – after all, they’re both created at the same time and cover the same period and location, with many other shared elements. This common pitfall can be avoided by thinking of them in terms of depth: a METAR is an at-a-glance weather report, whereas the ATIS broadcast contains everything the pilot needs.

Key Takeaways

In reading this introduction to flight planning and weather prediction, a few fundamental differences between METARs, TAFs, PIREPs, and ATIS reports emerge that inform the future pilot of the use cases for each type of report.

Timing

While METARs, PIREPs, and ATIS reports offer a snapshot of what the conditions are like at the moment they’re created, TAFs are more predictive in nature, forecasting conditions over a longer period to give the pilot a sense of what they will encounter in future. This allows the pilot to plan their imminent departure by looking at METAR and ATIS reports, check the METAR and TAF data of both their arrival airport and possible alternatives during the flight, and consult METAR, TAF and ATIS reports before beginning their descent.

Authorship

While METARs and TAFs originate from the ground staff charged with compiling them, PIREPs come directly from pilots who are in the air themselves at the time of writing. This means that they give an overview of the aerial conditions that is as accurate as possible for the pilot, highlighting key details that ensure the smooth operation of the flight. ATIS data is compiled hourly by air traffic controllers, providing a comprehensive rolling commentary of the conditions to be expected.

Use

The final area of difference between these reports is their use cases. Stemming from their function and the period of weather that they cover, each type of report fulfils a different purpose for the pilot.

The METAR gives a rough idea of what to expect, and is often checked before departure as part of a pre-flight briefing. The TAF is used to inform expectations of the flight due to the longer time period that it covers, while it’s also consulted to plan landing. PIREPs – depending on their urgency – can either give routine indications that everything is proceeding as planned or provoke the need for rapid changes in arrangements. Finally, ATIS is constantly churning away in the background, and is consulted for hour-by-hour data when performance calculations are being made – such as immediately before takeoff or landing.

With all that in mind, try testing yourself on some real-world PIREP, METAR, ATIS, and TAF examples by using decoding matrices or online tools to see if you can unpack the wealth of detail that they contain. Don’t worry if it’s too daunting for the time being – building familiarity is the first step on the road towards expertise, and you’re in safe hands the rest of the way with BAA Training!